Sahar Freemantle is an Anglo-Persian milliner. That means she designs and constructs hats. She is also a Baha’i.

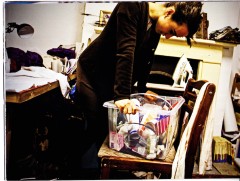

Residing in the up and coming London Borough of Hackney, Sahar musters up her hats and other fashionable creations from her East London workshop.

As the director of her own company; ‘UglyLovely,’ Sahar has featured in numerous publications, from fashion to local government.

Sahar, first of all thanks for joining us in the new Nineteen Months.

There is a well-known quote in the Baha’i Writings that says ‘man is a mine rich in gems of inestimable value, education alone can cause it to reveal its treasures…’ Therefore, what inspired you come to enter the millinery business? What was the educational process that gave you the skills?

After my A-levels [required for university entry], I knew I wanted to do something art related, but I didn’t know what. So I followed the usual path and did an art foundation course. When the crunch time came to make a decision as to what to study at degree level, I still didn’t really have a clue. I frantically started looking through art college prospectuses and saw a photo of a Victorian style costume made out of leather and I just thought ‘that’s cool, i want to be able to make things like that!’ After 3 years of very long hours in the studios working and generally having a lot of fun doing it, I’d completed my Bachelors degree in Performance Costume. Millinery didn’t come until a little while later, when I was helping out at a fashion show and the milliners backstage had some amazing creations which seemed to sum up every aspect of my degree that i loved. I then did some work experience with them, this wasn’t a formal education, but every bit as valuable.

Sahar, the U.K’s Guardian Newspaper stated in 2010 that the British Fashion industry is now worth nearly £21 Billion (>$30 Bn) a year. In such an industry, which end of the spectrum do you feel your designs fit into?

I’m curious to know how much of that [£21 Billion] comes from high fashion, and how much comes from cheap high street stores.

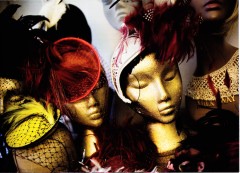

Although the high end designer stuff has exorbitant price tags which can only cater for the super rich folk, there’s something wonderful about appreciating a garment / accessory and almost treasuring it like a work of art – something I see people do with my hats, which brings me great joy.

On the other end of the scale, you get the cheap high street ‘bargains’, designed to be thrown away after one season. I’m not a fan of this ever growing consumer culture, the excessive materialism that’s bad for the environment and leaves people wanting more, barely able to control themselves in the stores because its all so cheap.

As always, I guess as Abdul-Baha says, the right path is moderation!

You obviously have passion in what you do, so what do you think ‘drives’ you?

What drives me is that I love glamour and I love people looking good! Wearing the right hat flatters and gives the woman added elegance and brings out confidence, this I feel is a sign of nobility. Yes, we’re a mine rich in gems, and education can help bring out those gems; but so can beautiful accessories!

Underlying it all, beauty and creativity are attributes of God. So if I create something beautiful, well at least those are two of His attributes I’m trying to reflect!

Sahar, whilst millinery is your main craft, you also do costume design. Recently you went to Mali, west Africa on a costume design job. Could you tell us about this trip and what your learnt from this international collaboration that you can take back to the U.K?

Yes, the job is costume designing for a Haitian dancer who lives in Mali and is performing in France. It’s for her next solo contemporary piece entitled ‘Je m’appelle Fanta Kaba’, which is about a prostitute called Fanta Kaba

It’s been great to work on an international collaboration and see how we can all cultures can contribute in a spirit of unity.

It was interesting because she knew she wanted a designer from London; she felt she couldn’t find what she was looking for elsewhere, not even in Paris. It was great to know London has a culture of its own and can offer things other places in the word can’t!

You say ‘Je m’appelle Fanta Kaba’ is about a prostitute. Have you found any conflicts in your Faith since taking this job on; do you feel that you are helping to glamorise one of the few professions that is contrary to the teachings of Baha’u’llah on chastity?

The piece explores culture and roots; letting go of one’s identity and being stuck in cross cultures. The story is told through the character of a prostitute called Fanta Kaba; a woman who has nothing left, no identity apart from her body. It is up to the audience to decide if we left with a vacant body, a victim and vulnerable – or a woman who is in control and using the only thing she has to her advantage.

The dancer wanted to explore different levels of selling oneself, even asking the question if dancing itself is a form of this; selling one’s body for the entertainment of others?

The piece is not condemning nor glamorizing the subject – but presenting it as a point of discussion. The idea is that Fanta Kaba could be from anywhere. Prostitution is probably found in every country of the world, it is a universal issue.

I feel that as a Baha’i, presenting this discussion in the form of asking questions, is not in any conflict with my Faith. I’m sure in time , the supreme body of our Faith, the Universal House of Justice, will tackle this issue but in the meantime if art can provoke a bit of healthy discussion I think that’s good!

Finally, you have been featured, as a young Baha’i designer, in Hackney, in a booklet produced by the British Youth Council, a charity founded by the U.K government working to ‘empower young people to have a say and be heard,’ can you tell us how you came to be involved in that and what that was all about?

It was a photography project about people from different cultures living in Hackney, and how they can be true to themselves and their culture when living in multicultural London. The photographer was interested in me as a Baha’i and if I find it challenging to live a Baha’i life here. In summary I pretty much said its not easy for anyone to have a high moral code. I think in the Baha’i writings it talks about feeling closer to God when in the countryside. I’m sure that’s true, but London’s not so bad – on the surface London might seem fast paced and materialistic, but dig a little deeper and there are spiritual ideas floating around, whether that be Karma, or wanting to serve humanity. If I’m open with my Faith it’s surprising how easy it is for other people to be open too.

You can see scanned excerpts from the interview with Sahar in the British Council sponsored ‘Youth in Action programme’ booklet on Hackney below and for more of Sahar’s work, check out her website; Ugly Lovely.

All photos in Hackney booklet are Copyright Francesco Stelitano